Opinions have differed for years about how to respond to children when someone close dies. Some will share with the child the probability that death is imminent, enabling goodbyes and help in designing the funeral, others believe they are protecting children by pretending all is well or not talking about illness or death.

Opinions have differed for years about how to respond to children when someone close dies. Some will share with the child the probability that death is imminent, enabling goodbyes and help in designing the funeral, others believe they are protecting children by pretending all is well or not talking about illness or death.

My experiences in children’s grief counselling, and as parish priest, were that children often handle the realities of sickness and death better than many adults. This led me to a research study that involved getting information from children themselves about their experiences when a parent died. This was the first such UK study to take the data directly from bereaved children. The children gave some very clear pointers.

About one third of those interviewed were warned that death was imminent, enabling sharing with the dying feelings and validations that will remain in the children’s memories all their lives. They expressed their belief that it was better to let things out than suppress them. Similarly, those who viewed the bodies of the deceased satisfied themselves that death had actually occurred, plus in one or two cases expressed pleasure at seeing how the pain of their illnesses had gone from the faces of the deceased.

One of the motivations I had for this survey was the distress I saw caused so frequently to children who were excluded from a parent’s funeral, while unknown family members and complete strangers attended. I compared the surprise and delight of children who were amazed at the number of people present, with the anger and distress of those excluded. As one Head Teacher (excluded when 13) put it: “I adored my gran. I still feel guilty at not saying goodbye.” There was also validation and appreciation at teachers and friends from school (some of whom knew the parent) attending.

Experiences varied on returning to school. Most wanted to return as soon as possible, getting back into safe routines after a trauma. Sadly some in the school saw this as an excuse for bullying or exclusion – “You can’t play with us, you’ve no mum”. Others treated the bereaved child as an invalid, but the support of “best friends” was appreciated and helpful.

A survey by a London hospice of over 200 schools showed that 60 per cent of teachers felt unclear as to how to respond to a bereaved child, one child reporting how a teacher had told him not to make a Father’s Day card as “You haven’t got a father”.

When it comes to family responses, evidence from other studies indicates that children’s adjustment from grief is helped by talking about the deceased. In my study, only one third found themselves able discuss the deceased with family, others found that adult members became too upset, or quickly changed the subject.

A child has a parent die every 27 minutes in UK, two million children aged from 5 to 15 have lost a close loved one, and many bereaved children see a GP in the 12 months before and after the death of someone close, often for no diagnosable reason. Can there be any dispute about responding appropriately?

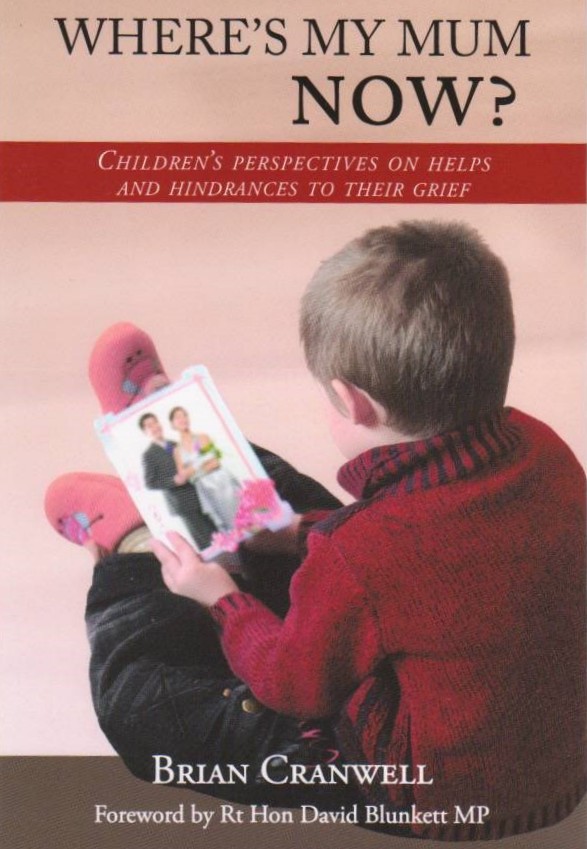

Rev Brian Cranwell MSc MPhil is the author of Where's My Mum Now?: Children's Perspectives on Helps and Hindrances to Their Grief and was the incumbent of a large parish in Sheffield for 13 years, a parish with seldom fewer than 140 funerals a year. During this time he was also Chairman of the Cruse Bereavement Care Sheffield branch, and a founder member of Sheffield based Gone Forever Trust.